Have you ever wonder why do you get some random noise in your Arduino ADC? Well, there could be a couple of reasons, but the most common one is an unstable voltage reference.

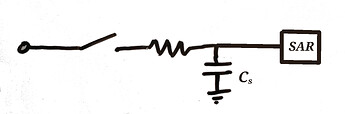

The ADC uses the 5V from the power source as a voltage reference when doing an AD conversion. If you measure the Arduino 5V pins, you will notice that the actual value fluctuates. So every time the Arduino performs a conversion, it compares the voltage at An pin against a different reference value.

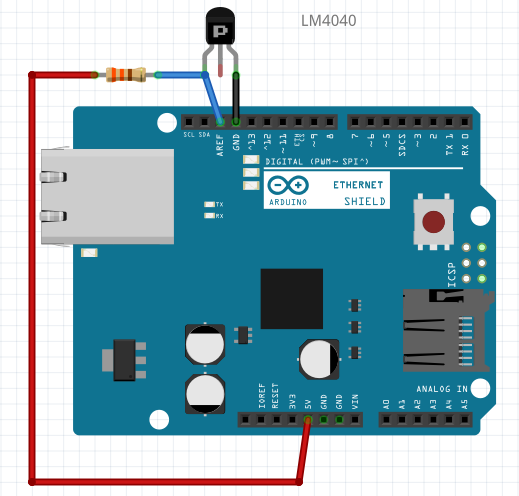

How do you solve that? The Arduino has an Aref pin to give the ADC an external voltage reference. If the voltage you are going to measure is guaranteed to be below 4V, then the LM4040 IC is a great option. This IC will give you 4.096V over a great range of temperatures and independently of the power source voltage.

The limiting resistor is recommended to be 909ohm, but 1K works well.

After adding the external reference, you need to tell Arduino to use external voltage reference:

analogReference(EXTERNAL)

Now, another advantage of the LM4040 is that conversion from ADC value (0 - 1023) to milivolts is straight forward! Just multiply the value you get from the ADC by 4 and that is the voltage at the An pin.

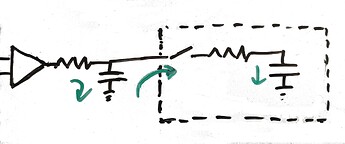

With this improvement you should get more stable readings. If you still get some random noise, there is one more thing you can try. The ADC_Sleep_Mode. In this mode, the Arduino turns everything off except the ADC, performs the conversion, and wakes up. This way, it avoids interference from internal signals Timers, PWM, etc.) during conversion. This is an alternative function to analogRead() that uses the sleep mode:

int getReading(const byte port)

{

ADCSRA = bit (ADEN) | bit (ADIF); // enable ADC, turn off any pending interrupt

ADCSRA |= bit (ADPS0) | bit (ADPS1) | bit (ADPS2); // prescaler of 128

ADMUX = (port & 0x07);

noInterrupts ();

set_sleep_mode (SLEEP_MODE_ADC); // sleep during sample

sleep_enable();

// start the conversion

ADCSRA |= bit (ADSC) | bit (ADIE);

interrupts ();

sleep_cpu ();

sleep_disable ();

// awake again, reading should be done, but better make sure

// maybe the timer interrupt fired

while (bit_is_set (ADCSRA, ADSC))

{ }

return ADC;

} // end of getReading

Some of the lines of code could be moved to your setup() function, but who wants those ugly lines in the setup anyway?

If you want some more information about this, you can check this issue.

We got our ph sensor working with a precision of ±0.01 with the improvements aforementioned.

Hope this results helpful!

Pablo